Los billetes y monedas de al menos ocho países africanos homenajean los proyectos de infraestructura chinos ejecutados en esas naciones, unos símbolos nacionales que evidencian la gran influencia del gigante asiático en el continente.

“Construir juntos un mundo mejor: China hace honor a ese compromiso en los billetes emitidos por sus amigos y socios de todo el mundo”, afirmó la embajada de China en Zimbabue en un mensaje de gratitud en la red X.

Marruecos, Argelia, Egipto, Sudán, República Democrática del Congo (RDC), Guinea-Conakri, Madagascar y Malaui son países que ensalzan en sus billetes y monedas los proyectos financiados por China como parte de su Iniciativa de la Franja y la Ruta.

“La percepción es que China está ganando influencia y, esencialmente, se está convirtiendo en parte de la vida cotidiana de los ciudadanos de los países afectados”, declara a EFE el analista keniano de relaciones exteriores y diplomáticas Eliud Kibii, sobre esa iniciativa.

El puente Kinsuka sobre el río Binza, levantado por la empresa de construcción China Railway Group en Kinshasa, capital de la RDC, se puede ver en un billete de 500 francos congoleños.

Guinea-Conakri muestra un proyecto chino, la central hidroeléctrica de Kaleta, en los billetes de 20.000 francos.

La Corporación China Tres Gargantas (CTG, por sus siglas inglesas) encabezó su edificación y la capacidad de producción de energía de la planta es de unos 965 gigavatios hora al año, según el Banco de Exportación e Importación de China.

En Malaui, la nueva sede del Parlamento, obra de la compañía china Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Group, figura en el billete de 2.000 kuachas.

Y en Egipto, por citar un último ejemplo, la moneda de 50 piastras lleva acuñada el distrito central de negocios de la nueva capital administrativa del país, de construcción china.

Estas infraestructuras no sólo implican el esfuerzo de China por afianzar sus relaciones con los países africanos, sino también un cambio en la tendencia de éstos por diversificar su dependencia de las grandes potencias.

“Son los chinos los que quieren que Kenia o África dependan de sí mismos”, afirma a EFE Lemmy Nyongesa, profesor de Diplomacia y Estudios Internacionales en la Universidad de Nairobi y arquitecto.

Nyongesa considera que la dependencia creada por Occidente fue “deliberada” y los líderes africanos ahora miran también a China.

“No cabe duda de que China quiere convertirse en una potencia mundial y, para ello, necesita aliados en todos los ámbitos, especialmente en África”, subraya Kibii.

La financiación china de todos estos proyectos, sin embargo, acarrea una dependencia que, en muchas ocasiones, conlleva el pago de deudas elevadas.

Según afirmó en un informe en noviembre de 2023 el Fondo Monetario Internacional (FMI), los préstamos chinos a África subsahariana «aumentaron rápidamente en la década de 2000», y la participación de Pekín en la deuda pública externa total de la región «saltó de menos del 2 % antes de 2005 al 17 % en 2021».

El principal reto para estos países africanos en sus relaciones con el gigante asiático, según Kibii, son “las negociaciones de préstamos, la consiguiente carga del préstamo y la rendición de cuentas de los préstamos contraídos”.

El Foro de Cooperación China-África (FOCAC) que se celebró del 4 al 6 de septiembre pasado en Pekín, al que acudieron 50 naciones africanas, evidencia el interés del país asiático por cuidar las relaciones el continente.

En Kenia, el director ejecutivo del Centro China-África del Instituto de Política Africana, Dennis Munene, recalca a EFE en Nairobi que este foro fortaleció las relaciones de los países africanos con Pekín.

“El desarrollo de infraestructuras ha servido para consolidar esta asociación bilateral entre China y muchos países africanos”, añade Munene.

China, que se ha convertido en el mayor socio comercial de la región gracias a los lazos económicos afianzados en los últimos 20 años, también está detrás de dos grandes infraestructuras en Kenia.

El ferrocarril que conecta la ciudad costera de Mombasa con la capital, Nairobi, y la autopista de Nairobi, que agiliza el tráfico y simplifica el trayecto hasta el Aeropuerto Internacional Jomo Kenyatta, son construcciones financiadas por China.

Nyongesa cuenta que, si no fuera por la entrada de China en el sector de las infraestructuras en este país del este de África, todavía tardaría doce horas en viajar desde Nairobi hasta su casa en un pueblo rural cerca de Eldoret (oeste).

“Pero hoy en día -concluye-, me lleva unas tres, cuatro horas en coche; y entonces sabes que (China) tiene un gran impacto”.

Cristyina Ondó

Fuente: https://www.infobae.com/america/agencias/2024/11/16/billetes-y-monedas-de-africa-ensalzan-proyectos-de-china-simbolos-de-su-gran-influencia/

BANKNOTES AND COINS FROM AFRICA PRAISE CHINESE PROJECTS, SYMBOLS OF ITS GREAT INFLUENCE

The banknotes and coins of at least eight African countries pay homage to Chinese infrastructure projects carried out in those nations, national symbols that show the great influence of the Asian giant on the continent.

“Building a better world together: China honors that commitment in the banknotes issued by its friends and partners around the world,” said the Chinese embassy in Zimbabwe in a message of gratitude on the X network.

Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Guinea-Conakry, Madagascar and Malawi are countries that praise projects financed by China as part of its Belt and Road Initiative on their banknotes and coins.

“The perception is that China is gaining influence and, essentially, is becoming part of the daily lives of the citizens of the affected countries,” Kenyan foreign relations and diplomatic analyst Eliud Kibii told EFE about this initiative.

- TAIWAN

LA INCLUSIÓN DE TAIWÁN EN LA LISTA DE SEGUIMIENTO DE LA MONEDA ESTADOUNIDENSE «PODRÍA CONVERTIRSE EN UNA RUTINA»

El Banco Central de la República de China (Taiwán) ha dicho que espera que la inclusión de Taiwán en la lista de vigilancia monetaria de Estados Unidos se convierta en algo habitual.

Los comentarios del banco central local se produjeron cuando el Departamento del Tesoro de EE.UU. volvió a colocar el jueves (hora de EE.UU.) a Taiwán en su lista de principales socios comerciales que merecen especial atención a sus prácticas monetarias y políticas macroeconómicas.

El banco central de Taiwán dijo que los canales de comunicación entre Taiwán y Estados Unidos estaban bien fundamentados para permitir que ambas partes tuvieran intercambios de visión integrales para una mejor comprensión de las políticas económicas y cambiarias de cada parte.

También se incluyeron en la lista de vigilancia del Departamento del Tesoro de Estados Unidos a China, Japón, Corea del Sur, Singapur, Vietnam y Alemania, de acuerdo con la Ley Ómnibus de Comercio y Competitividad de 1988 aplicada por el informe, que analizó las prácticas de los principales socios comerciales de Washington.

Esta es la sexta aparición consecutiva de Taiwán en la lista semestral.

Pan Tzu-yu and Frances Huang

Fuente: https://focustaiwan.tw/business/202411160009

TAIWAN’S INCLUSION ON U.S. CURRENCY MONITORING LIST ‘COULD BECOME ROUTINE’

The Central Bank of the Republic of China (Taiwan) has said it expects Taiwan’s inclusion on the United States’ currency monitoring list to become a regular occurrence.

The local central bank’s comments came as the U.S. Department of Treasury on Thursday (U.S. time) again placed Taiwan on its list of major trading partners that merit close attention to their currency practices and macroeconomic policies.

Taiwan’s central bank said communications channels between Taiwan and the U.S. were well founded to allow both sides to have a comprehensive view exchanges for a better understanding of each side’s economic and foreign exchange policies.

Also included on the U.S. Department of Treasury’s watchlist were China, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Vietnam, and Germany, in accordance with the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 applied by the report, which analyzed the practices of Washington’s major trading partners.

This is Taiwan’s sixth straight appearance on the twice-yearly list, while South Korea returned to the list for the first time since November 2023.

None of Washington’s major trading partners was named a currency manipulator, referring to those economies believed to be taking advantage of manipulation of the exchange rate between its currency and the U.S. dollar for purposes of preventing effective balance of payments adjustments or gaining unfair competitive advantage in international trade during the four quarters through June 2024, the U.S. Treasury said.

The U.S. Treasury report uses three criteria to determine which trading partners will be named as currency manipulators.

The three criteria include a bilateral trade surplus with the U.S. hitting at least US$15 billion and a material current account surplus accounting for at least 3 percent of an economy’s gross domestic product (GDP).

The third is designed to assess whether an economy gets involved in persistent one-sided intervention in the foreign exchange market when net purchases of foreign currency are conducted repeatedly, in at least eight out of 12 months, with these net purchases making up at least 2 percent of its GDP over a 12-month period.

When an economy meets two of the three criteria, it will be automatically put on the watch list.

When an economy meets just one of the three criteria for two currency reports in a row, it will be removed from the monitoring list.

If an economy meets all three criteria, it will be named a currency manipulator.

The local central bank said Taiwan met the first two criteria as the country enjoyed a trade surplus of US$57 billion during the four quarters to June, and a surplus in its current account, which mainly measures the exports and imports of a country’s merchandise and services, was equivalent to 14.7 percent of its GDP.

The central bank said that as Taiwan is an export-oriented economy and demand for Taiwan-made information and communications items from the U.S. market is robust, a trade surplus with the U.S. has been on the rise.

Since 2018, the local central bank said, Taiwan’s increasing trade surplus with the U.S. largely reflected demand for gadgets in particular chips used in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence applications.

Other factors included business opportunities created by remote working and schooling, and escalating trade tensions between Washington and Beijing, it added.

Therefore, the growth in trade surplus with the U.S. has had nothing to do with any currency manipulation, the local central bank said.

The central bank added that Taiwan’s large current account surplus largely reflected the country’s huge accumulated excess savings.

In a written report submitted to the Legislative Yuan earlier this week, the central bank suggested Taiwan expand its purchases of energy and agricultural goods as well as military items from the U.S. in a bid to reduce a trade surplus.

The U.S. Treasury said in the report that Taiwan should closely monitor non-bank financial sector risks, including foreign exchange risks, while foreign exchange intervention should be limited and allow currency movements in line with economic fundamentals.

- TRANSPACIFIC

TERMINAR EL VACÍO ESTRATÉGICO: UNA ESTRATEGIA DE EE.UU. PARA CHINA EN AMÉRICA LATINA

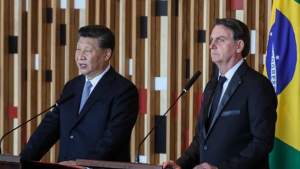

Las alarmas están sonando en América Latina. La reciente visita del presidente chino Xi Jinping a América Latina culmina una década de avances notables para China en la vecindad compartida de Estados Unidos. Tanto Xi como el presidente Biden asistieron al foro de Cooperación Económica Asia-Pacífico (APEC) en Lima, Perú. Luego, ambos viajaron a Brasil para la reunión de la Cumbre del G20. Las imágenes públicas de las dos reuniones dijeron mucho sobre el avance de China en América Latina con poco o ningún retroceso de Estados Unidos.

Las alarmas están sonando en América Latina. La reciente visita del presidente chino Xi Jinping a América Latina culmina una década de avances notables para China en la vecindad compartida de Estados Unidos. Tanto Xi como el presidente Biden asistieron al foro de Cooperación Económica Asia-Pacífico (APEC) en Lima, Perú. Luego, ambos viajaron a Brasil para la reunión de la Cumbre del G20. Las imágenes públicas de las dos reuniones dijeron mucho sobre el avance de China en América Latina con poco o ningún retroceso de Estados Unidos.

Los organizadores dicen que la foto final del grupo APEC colocó a los líderes en orden alfabético, con Xi Jinping junto a los líderes de Canadá y Chile, pero también podría haber sido una metáfora de la menguante influencia estadounidense y la falta de estrategia en América Latina. Biden se colocó en la última fila, lejos de la presidenta peruana Dina Boluarte. Mientras tanto, Xi sonrió en la primera fila junto a su anfitrión peruano. Más allá de la participación de Xi en las reuniones de APEC, también inauguró un megapuerto de aguas profundas de 3.500 millones de dólares en Chancay, justo al norte de Lima. Este proyecto de la Iniciativa de la Franja y la Ruta (BRI) aumentará la conectividad entre Beijing y América del Sur, reduciendo los tiempos de envío de productos agrícolas y minerales en aproximadamente 10 días y evitando paradas en México o Los Ángeles. Al ofrecer una ruta marítima directa desde América del Sur a China continental, Chancay servirá como punto de apoyo de un floreciente corredor marítimo-terrestre entre China y América Latina. China dice que esto beneficiará no sólo a Perú sino también a los países vecinos, con proyectos de infraestructura planificados que permitirán a Brasil, Chile, Ecuador y Colombia aprovechar también el puerto.

Ryan C. Berg

Fuente: https://www.csis.org/analysis/ending-strategic-vacuum-us-strategy-china-latin-america

ENDING THE STRATEGIC VACUUM: A U.S. STRATEGY FOR CHINA IN LATIN AMERICA

The alarm bells are ringing in Latin America. Chinese president Xi Jinping’s recent visit to Latin America caps off a decade of remarkable advances for China in the United States’ shared neighborhood. Both Xi and President Biden attended the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in Lima, Peru. Both then traveled to Brazil for the G20 Summit meeting. The public imagery of the two meetings said a lot about China’s advance in Latin America with little to no U.S. pushback.

Organizers say the APEC group photo placed leaders in alphabetical order, with Xi Jinping next to leaders from Canada and Chile, but it might as well have been a metaphor for waning U.S. influence and lack of strategy in Latin America. Biden was placed in the back row, far from Peruvian president Dina Boluarte. Meanwhile, Xi beamed in the front row next to his Peruvian host. Beyond Xi’s participation in APEC meetings, he also inaugurated a $3.5 billion deepwater megaport in Chancay, just north of Lima. This Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) project will increase connectivity between Beijing and South America, trimming shipping times for agricultural and mineral commodities by about 10 days and avoiding stops in either Mexico or Los Angeles. Offering a direct shipping lane from South America to mainland China, Chancay will serve as the fulcrum of a burgeoning maritime-land corridor between China and Latin America. China says this will benefit not just Peru but also surrounding countries, with planned infrastructure projects allowing Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, and Colombia to leverage the port, too. Previous CSIS research utilizing satellite imagery has also highlighted Chancay’s potential for dual use. The berths at the port are wide enough for the People’s Liberation Army to dock naval vessels, something that has raised the concerns of the U.S. Southern Command.

To sum up the bad news of the past decade—the opening of Chancay is the culmination of more than a decade of ceding influence to China in Latin America. Trade between Beijing and the region grew tenfold over the past two decades, and China has emerged as the second-largest trade partner for the region after the United States. When factoring out Mexico, China easily takes the number one spot. Since 2018, 22 of 26 eligible countries have joined China’s signature BRI, and the holdouts, large countries like Brazil and major U.S. trade partners like Colombia, are openly contemplating BRI accession. The region has formed a core part of China’s Global South strategy, remaining “non-aligned” while pursuing the reform of international organizations and spearheading alternative visions of global order with institutions such as the BRICS.

To sum up the good news of the moment—the secretary of state nominee, Senator Marco Rubio, has spent much of his time in the Senate thinking about Latin America, and the incoming national security adviser, Representative Michael Waltz, understands the region and speaks frequently about its dynamics. In a world with active conflicts in multiple other theaters, the Trump administration is still poised to pay lots of attention to Latin America. Its legacy in the region could—and should—be placing the United States on a more competitive path with China in Latin America through the development of a U.S. strategy for China in the region.

Rapid and Dramatic Advance

China has advanced rapidly in just about every corner of the region, including in highly strategic ways that go beyond mere increases in bilateral trade. Here are a few salient points:

China has the largest amount of space infrastructure outside of mainland China in Latin America and the Caribbean. Of particular concern is Espacio Lejano, the deep space station that effectively operates like a sovereign slice of Chinese territory in the Argentine Patagonia. Yet, China operates or has access to around a dozen other facilities throughout the hemisphere.

Chinese state-owned enterprises dot the region, with electric vehicles being a particular focus of recent activity. Electric vehicle giant BYD has announced interest in opening factories in several countries, including Mexico. China’s large construction giants are very active in the region, as are its mining operations. A handful of countries maintain trade agreements with China, and several more have commenced negotiations on trade agreements with China.

China maintains contracts to upgrade or operate more than three dozen ports in the region, including potential dual-use deepwater ports. There are both military and commercial implications. China may seek to leverage its port infrastructure in a conflagration over Taiwan. Short of war, however, China gains significant commercial surveillance capabilities by owning and operating ports in Latin America—surveillance that can undercut U.S. business in the region and crossover to have military application. The ability to renovate, upgrade, and operate ports provides China with a concerning level of control over customs and security, giving rise to concerns about organized crime activity, such as the import of chemical precursors for synthesizing fentanyl through Chinese-operated port terminals in Mexico. According to information from Mexico’s Secretariat of Defense, 273 million dosesof fentanyl were seized between 2015 and 2023 and were trafficked through the Mexican ports of Lázaro Cárdenas, Manzanillo, and Ensenada. The same concern about attracting organized crime groups applies to the Chancay port in Peru.

China was an early investor in Latin America’s critical minerals space. Through long-term offtake agreements, it has rewired much of the region’s mineral trade toward China, where it is refined and then exported—often back to Latin America—at a markup. Chinese mining companies have won concessions in all the region’s important mining powers. Control over extraction, and especially refining, gives China a key chokehold on the minerals supply chain.

Although the United States remains the preferred defense partner, China has increased exchanges with Latin American armed forces. Recently, Brazil and China held joint military exercises, simulating an amphibious invasion. The operation carried the unfortunate name “Operation Formosa.” The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has imitated the United States in offering international military education and training to regional armed forces, providing an opportunity to grow influence networks and exchange on topics like training and doctrine. China has also sensed an opening to compete with the United States by increasing police cooperation on civilian security matters. Representing just 8 percent of the global population but about one-third of global homicides, Latin America remains uniquely vulnerable to China’s offer of cooperation on citizen security.

Latin America remains the most important region of the world for Taiwan and its formal diplomatic allies. Yet, Taiwan has lost five of its formal diplomatic allies in the last seven years—Panama, El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and Honduras. Flipping the remaining seven diplomatic allies in the Western Hemisphere remains a top PRC goal in the region.

China has lent its support to some of Latin America’s most brutal authoritarian regimes. Venezuela, Nicaragua, Cuba, and Bolivia all count China as major economic and security partners. As previous research from CSIS demonstrates, China’s expansion in the region has coincided with massive declines in the quality of governance and democracy. The research shows that this may be far more than a coincidence, with China’s engagement contributing to democratic backsliding in Latin America.

While Antarctica remains a zone of peace governed by the Antarctic Treaty, recent Chinese actions have given Antarctic powers pause. In 2014, Xi Jinping declared China’s intention to become a “polar power.” Since then, China appears focused on building a larger presence on the continent, possibly leveraging research activity as cover to map mineral and energy deposits.

Beyond these specific projects, of note is China’s advance in U.S. partner countries, as well as those that set out to decrease the role of China in their economies and shun Chinese investment where possible. Mexico comes immediately to mind in the category of partner countries. The United States’ largest trading partner has seen growing Chinese influence lately. Last year, Chinese companies announced nearly $13 billion in new investments, and there are well-founded concerns about the undercounting of Chinese investment. The Rhodium Group estimates that Chinese investment in Mexico may be six times higher than the level shown in official government statistics, lending credence to U.S. and Canadian concerns regarding a Chinese “backdoor” via the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement to circumvent tariffs on imports.

Colombia is another country in the former category of partner countries. Often referred to as the linchpin and the United States’ greatest strategic ally in the region, the election of leftist president Gustavo Petro has been a game changer for China-Colombia relations. Beyond an uptick in trade flows—China will soon overtake the United States as Colombia’s largest trade partner—Colombia under Petro has expressed an interest in acceding to the BRI and joining the BRICS Bank. The country seeks up to $40 billion in climate financing and has said it will go to China if the United States is unwilling to partner. Key infrastructure projects, such as the Bogota metro, will be built by Chinese state-owned enterprises.

In Argentina, President Milei came to power criticizing China and vowing to reduce the country’s influence. Furthermore, the libertarian president has sought a close working relationship with President Trump. However, he now calls the PRC an “interesting trade partner” and held a bilateral meeting with Xi at the recent G20 Summit. The PRC maintains a direct credit line between the Chinese central bank and Argentina’s central bank, furnishing it with considerable influence over Argentina’s ability to pay back the International Monetary Fund.

In other countries, unforced errors have contributed to diminished U.S. influence. In Guyana, the world’s newest petro state, the Biden administration blocked $180 million in infrastructure financing through the Inter-American Development Bank. Guyana’s remarkable economic growth—last year, it was the world’s fastest-growing economy—has been catalyzed by major offshore oil discoveries, the reason the Biden administration blocked the loan. China has since filled the void, which is all the more frustrating given Exxon Mobil made the original oil discovery, and the consortium that will soon be pumping nearly one million barrels of oil per day includes Hess Corporation, another U.S. company. These wounds are of the self-inflicted variety.

While Brazil declined to join the BRI at the recent G20 Summit, the country “recognized the relevance” of the initiative and is likely to join in the future. Still, China and Brazil signed nearly 40 agreements at the G20, hailing a “new phase” in their bilateral relationship. Beyond trade, the two countries are accelerating cooperation in sensitive areas such as space exploration, with Chinese commercial space companies set to launch satellites from Brazil’s Alcantara Space Station.

In Need of a Strategy

Simply put, the United States can no longer afford to engage in strategic neglect of its own shared neighborhood. For too long, China has been able to advance its geopolitical aims in a near strategic vacuum. For too long, the Chinese offer has been the best offer for partners and allies—too often because it has been the only offer.

Any realistic strategy must start by recognizing several things. First, China is here to stay in Latin America. An effective U.S. strategy cannot have as its goal extricating China from the region. Second, an effective U.S. strategy must preserve core U.S. interests in Latin America and play to both the regions and the United States’ strengths. The region must remain a hub of vibrant democracies driven by market economies. Political and economic models that are explicitly anti-Western should find no safe haven in the Western Hemisphere.

With these principles in mind, in previous work, CSIS has outlined a grand strategy for addressing China in Latin America that can be summarized: insulate, curtail, and compete.

Insulate: China is a coercive actor. The PRC often seeks to coopt political leaders, utilize the weight of the Chinese economy, and/or punish those it sees as overly critical or disloyal. These strategies can be especially baleful in unconsolidated and developing democracies. In this context, the United States must identify vulnerabilities in Latin American democracies that the Chinese Communist Party is likely to exploit, and it must insulate those vulnerable points to keep China from making large strategic gains. Such examples include opportunities for corruption and cooptation in procurement and the tender process for large infrastructure projects. China’s authoritarian nature has not prevented it from developing a nuanced understanding of the dynamics present in Latin America’s democracies. Forcing China to settle for strategies that would, at best, see the PRC make incremental gains in Latin America would be a massive improvement over current policy, affording the United States more space and time to compete effectively.

Curtail: The biggest cliché about China’s presence in Latin America is that “countries do not want to choose between partners.” While the United States should not be in the habit of dictating Latin America’s trade partners, there are select areas where both the U.S. and the regional strategic interest should be overriding. The strategic community has not found consensus on exactly which areas, but one is slowly coming into focus: semiconductors, telecommunications, artificial intelligence, green technology, critical minerals, and cloud computing, among others. In short, sectors where dominance in the industry will help to write the future rules of global economic governance.

In these select areas, the United States should demand Latin American countries make strategic choices—and lay out those choices clearly. Seeking to curtail Chinese activity in the region could easily backfire, so keeping this area circumscribed and marrying it with competition is key.

Competition: The United States has more free trade architecture in Latin America than any other region of the world. It has an array of development agencies at its disposal to galvanize investment and private sector interest, such as the U.S. Development Finance Corporation. And it possesses the largest number of voting shares in multilateral financial institutions, such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and Inter-American Development Bank, that can catalyze investment. When the United States seeks to curtail Chinese investment and activity in key industries, it must compete to put a viable, cost-competitive alternative on the table. If it does not, countries in the region will interpret our presence as filled with moral lessons but little else. In some cases, that alternative might be American, but it just as often might not be. The United States should work to bring more Japanese, Korean, Taiwanese, and European investment to the region, especially in sectors where the United States is less likely to invest or where partner countries can bring their comparative advantages.

The next administration will face daunting international tasks. Resolving conflicts in multiple theaters will require considerable energy and political will. Yet, China’s advance in the United States’ shared neighborhood should be of critical concern. The bad news is how dramatically China has grown its presence in recent years; the good news is that it is not too late to push back and regain the U.S. foothold. The Trump administration should leave a legacy of placing the United States on a more competitive footing with China in Latin America.

Monitor 2049®

Editor: IW, senior fellow of REDCAEM (Red China – América Latina) and CESCOS (Center for the Study of Open Contemporary Societies)

Contact: iw@2049.cl

Monitor 2049® -Entendiendo geopolíticamente a China & Taiwan- es un canal digital que se hace eco de una fecha simbólica en la perspectiva de los grandes cambios mundiales. Los ejes de poder global se consolidarán en el área del Pacífico, particularmente en torno a China, provocando transformaciones que marcarán el rumbo del siglo. 2049® da cuenta de los escenarios nuevos y en proceso de configuración.

Para ello, siguiendo la editorial de Nuevo Poder, registra materiales periodísticos de fondo -léase reportajes de investigación, entrevistas, historias de portada, columnas de análisis- así como papers académicos, referidos a tales asuntos, los que se recogen semanalmente en español e inglés.

—

Monitor 2049® -Understanding geopolitically China & Taiwan- is a media outlet, which echoes a symbolic date in the perspective of the upcoming changes worldwide. The axes of the global power will be consolidated in the Pacific area, particularly around China, causing transformations that will mark the course of the century. 2049® tracks these new and ongoing scenarios.

To do this, following the editorial of Nuevo Poder, it will track background journalistic materials -investigative reports, interviews, cover stories, op-eds – as well as academic papers referring to such topics, records that are collected weekly in Spanish and English.